How do you have an honourable resignation?

- Published

- comments

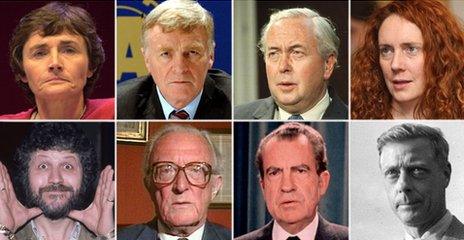

There have been numerous high-profile resignations recently. Some hang on until the bitter end and some leave under a cloud but is there a way to go with grace?

The way someone leaves a job can affect their career forever.

When some resign they leave with their heads hung in shame, for others it's a moment of defiance, and there are those who acknowledge that they have done wrong and leave quietly.

Some are seen to have waited too long.

"I'm not a crook," said President Richard Nixon during the Watergate scandal that led to him stepping down.

Many felt Nixon hung on in an undignified manner, going only when it seemed clear he would otherwise be impeached. His departure speech contained no mea culpa, leaving the allegations against him - of involvement in the Watergate burglary cover-up - unresolved.

But if someone holds their hands up when they get it wrong, a quick resignation can work in someone's favour.

Sir Paul Stephenson, the former Met Police commissioner resigned rapidly in the wake of the phone-hacking scandal, and insisted he was leaving with his integrity intact. His resignation was called "honourable and shocking" by MP Keith Vaz.

So what constitutes an "honourable" resignation?

The media might dwell on the miscreant ministers who have hung on like barnacles, but there have been many who have chosen to resign on principle.

Following the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands in 1982, Richard Luce, then minister for state for foreign affairs, went to see Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington to resign from his post.

"Before I could say anything, he saw my face and said 'you're not going to resign'," he says.

"So I told him the reasons and he said 'no, hang on, I'm the foreign secretary, I carry the can. You're my minister of state and it's our duty to stay at our posts'."

But that did not last for long. As the press turned against the government and public unrest grew, Lord Carrington resigned along with two of his junior ministers on the principle of ministerial mismanagement.

"MPs from all parties came up privately and said 'thank you for doing that and there but for the grace of God go I'," Luce says.

"It made me feel that principled resignation as a matter of honour was good for our democratic system."

In more recent times, Robin Cook resigned over the Iraq War in a statement that earned him a standing ovation in the House of Commons.

And David Davis, then shadow home secretary, resigned from the shadow cabinet and as an MP to provoke a by-election as a referendum of 42-day detention legislation.

It was called a "stunt that has become a farce" by then Prime Minister Gordon Brown but a few, including Fraser Nelson of the Spectator, believed he was was doing it for all the right reasons.

Davis later regained his seat but has still yet to regain his place in cabinet.

But, away from politics, perhaps the biggest resignation in living memory was the abdication of King Edward VIII. On 10 December 1936, the king signed away his right to the throne in the name of love. His chosen partner, Wallis Simpson, was not only an American, but an American divorcee.

Unacceptable to the powers that be, the choice was eventually either give up Simpson or give up the throne.

They remained married until Edward's death in 1972.

While many choose to go quietly, others refuse to go without making their views known. And few ways are more obvious than making that resignation on air.

In 1993, Radio 1 DJ Dave Lee Travis chose to make his resignation public on his radio show. He was upset about the way the station was heading and there were rumours that he was going to be pushed out in a station re-shuffle.

"Changes are being made here which go against my principles," he said.

He was not the first British radio presenter to resign on air. Radio Lancashire's Terry Durney, known as Terry the Post to his colleagues because of his parallel career as a postman, picked his moment in 1991 to voice his discontent about the station moving towards more discussion-based programming.

'Downward spiral'

Resignations have sometimes been used as a kind of protest, something that has become increasingly common over recent decades.

Journalist Stephen Pollard inserted an obscene acrostic message to new owner Richard Desmond in his last leader column for the Daily Express. But the stunt led to a job offer at the Times being withdrawn.

Fellow journalist Richard Peppiatt resigned from the Daily Star, saying he was tired of making up stories and arranging for his resignation letter to be printed in the Guardian. The Daily Star said he couldn't resign as he was only a "casual" in the first place, and suggested he had become disgruntled at not getting a staff job.

"March 1 was going to be the day that I did it," Peppiatt says. "Partly because it was the day I got paid, I wanted to make sure I got my expenses for the last two months and my wages. For about 30 seconds [after sending it], I was uncontrollably sobbing. You hadn't just burned your bridges, you'd gone back and strafed them for good measure."

If a resignation is not done quickly, the negative attention can damage someone's career permanently.

But sometimes, when faced with pressure to go, those in the firing line - or more correctly in the resignation line - think that carrying out the job they are meant to do is the only honourable thing.

Former FIA president Max Mosley was facing pressure after a newspaper revealed his participation in a sado-masochistic sex session with five women. Despite a wave of criticism, he decided to stay in his post until the end of his term.

"There are situations where you're in charge, it's not your fault but you have to resign," he says.

"I think if there'd been a big accident in Formula 1, with part of the car going in the crowd or something serious like that, I would have felt probably I ought to resign or at least offer my resignation.

"If I had resigned, I don't think it would have been an honourable resignation, I think it would have been a cowardly resignation because I'd done nothing wrong. I hadn't done something I shouldn't do, which is when you should resign. This was something to do with my private life."