In thought, word and deed, Michael Foot was bold and brilliant. His fidelity to convictions and to comrades was unswerving. He carried hot ideas in a cool head. He never bragged nor blustered. He was learned but never obscure, erudite but never preening, principled but never precious, courteous but not deferential, provocative but not vindictive, creative but not abstract – "Assess and describe the challenges by all means," he said, "but don't confuse analysis with action. The one must lead to the other if it is to be useful to people." To him, socialism was the enabler of liberty and creativity, never the creed of conformity or obedience, and his socialism was inseparable from democracy as the means to power and the purpose of power.

To Michael, laughter was always the sharpest political weapon, and he was a master of mockery. Michael Heseltine, scuttling between opposing and supporting Margaret Thatcher was told that he could "rat, but not re-rat". The supercilious David Owen was reduced to rubble with "perspicacious advice from Miss Zsa Zsa Gabor – macho ain't so mucho". Scottish Nationalist MPs, about to follow Donald Stewart into the Tory lobby to bring down the devolutionist Labour government in 1979, should offer him: "Hail, Caesar, we who are about to die salute you!" And when, that same night, Liberal MPs were going to ensure victory for Mrs Thatcher, they were led by "the boy, David [Steel], who has passed from rising hope to elder statesman without any intervening period".

The fact that all of his speeches were made without a note won admiration from enemies as well as supporters. In the wake of one pyrotechnic bout, I complimented him on the effectiveness of his rhetorical pauses and said that maybe he should have been an actor. "No good," he said, "Those pauses aren't dramatic. They are asthmatic."

He was a man of passions. They ranged from his beautiful, adored Jill – top of any list of loves – to Plymouth Argyle, and from Hazlitt and Mozart to Humphrey Bogart.

He was assertive, and often granite stubborn, but completely devoid of vanity. And his most self-sacrificing act in a life free of selfishness was – when fulfilling years of writing and reflection beckoned – to agree to become leader of the Labour party at the age of 67. He did that in response to the urgings of friends who believed that his capacity to inspire would pull a faction-riven Labour movement back into coherence.

I was not among those who appealed to him to stand. I thought that, even if he won, he would be submitting himself to endless torture. And he was subjected to agony, as the self-indulgence of some on the left and desertion by some on the right enfeebled Labour, gave comfort to Thatcherism and generated poisonous treatment by the press. And yet, even Michael's most vitriolic critics would have to concede that his dedication, endless patience and raw courage saved the party from terminal division.

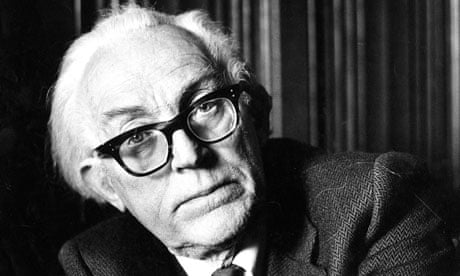

Michael Foot gave love and earned love as few politicians do in any age. Part of that was the result of his huge political and intellectual generosity. Much of it came from his ability to uplift people. Some will recall him as the walking-stick waving, wild-haired old man of cowardly caricature. More perceptive people will remember an irrepressibly valiant champion of freedom and justice who put his great intelligence and radiant wit to their best use – the emancipation of others.

Michael's religion was humanity. His country was the world. He was a citizen of the community formed through the ages by the best radical and cultured spirits within and beyond these British Isles. He served all with undeviating loyalty and a daring vigour that ignited causes and minds.

The only tribute he would want, the only memorial that will do him justice, is pursuit of progress that enlarges human liberty. Let us give him that, and by doing it illuminate the future.