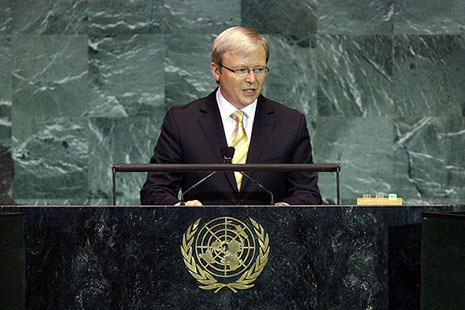

WHY, AFTER being elected with such high hopes, has Kevin Rudd’s star fallen so fast? We all know the events: the failure to negotiate the emissions trading scheme through the Senate and the decision to drop the policy until after the next election; the disastrously handled insulation scheme and the lesser disaster of Building the Education Revolution; the decision in an election year to take on one of Australia’s most powerful interests, mining, with a new tax. And then there’s the increasingly annoying manner, with the repeated tag lines, the priggish, robotic delivery. It’s only my professional commitment to following Australian politics that stops me from leaving the room when he appears yet again in a hard hat and fluoro safety jacket, or sitting in his shirt sleeves beside a hospital bed chatting with studied informality. And if, as the polls indicate, most Australians have switched off too, then his capacity to regain lost ground is very weak. It is as if he is fading from view before our eyes, still talking, a less and less substantial figure, like the Cheshire cat but with pursed lips and a wagging finger.

The title of David Marr’s June Quarterly Essay, Power Trip, points to some answers. Rudd began his maiden speech in federal politics with the words “Politics is about power.” Well, yes and no. Power is complex. It comes in many forms, from coercive power, with its threats and bribes, to the authority to give orders and expect to be obeyed, to the power to persuade people to see a situation as you do and agree with your line of action. And in liberal democracies like Australia, the power of any one political officeholder, even the prime minister, is limited. Marr quotes a shrewd old bureaucrat who has worked with a few prime ministers and wonders if Rudd really understands the way power works at the top. “He isn’t afraid to pick a fight, but doesn’t then behave like a prime minister: he involves himself so much; puts himself on the line so quickly; doesn’t exercise authority by keeping at a distance.”

This is Rudd of “the buck stops with me,” who presents himself as the fixer of last resort of all the nation’s problems. This is the Rudd who rushed in to take the blame for all the problems of the insulation scheme, and whisked his notebook out of his top pocket to note down the names of worried insulators, reassuring them that there would be another phase of government largesse once the problems were sorted out. Why did he think he had to take all the blame? There were a few other candidates – like shonky small business operators. And no one really expects the PM to act as everyone’s local member, sorting out each person’s problems with this or that government scheme. But having promised something he then found he couldn’t deliver, and he only has himself to blame when he walks away and people are angry. There is a failure of judgement here as he promises too much and delivers too little, both in small things like the promise to the insulators and in large policy reversals like the emissions scheme. I am sure we will see a similar pattern in his attempt to fix the blame game in the nation’s hospital system.

Implicit in these failures of judgement is a fantasy of concentration of power in the office of the PM. Bucks stop – or not – in many places in liberal parliamentary democracies like ours: in particular with individual ministers, with state premiers and, behind the scenes, with senior public servants. Marr shows convincingly that Rudd is driven by a genuine and deeply held commitment to making Australia a decent place for children to grow up in, a commitment forged in the hard years after his father died. Because his father was a tenant farmer, the family lost its home after he died, and he endured two terrible years as a boarder in a Marist College that instilled in him an icy hatred of the school. Rudd’s determination to make Australia a place in which kids didn’t have to suffer like he had was accompanied by a determination to re-make himself from a fussy little kid on the margins of other people’s lives into someone who was both unassailable and at the centre of things – which is where, he thinks, he now is.

But the problem is that, having got there, his hold on power is slipping faster than anyone could have imagined. He has become, Marr argues, the choke point in the government, just as he was in Goss’s government when he ran the cabinet office. Rudd’s micromanagement and need to be on top of every detail also has to do with owning all the outcomes of government; he treats senior public servants as underlings, patronises caucus, ignores advice and bypasses his ministers, hogging all the big announcements for himself. And, in the judgement of a former staffer, “For all the effort he doesn’t come up with particularly interesting solutions to problems. His policy positions aren’t breakthrough, not particularly new or exciting. After all that work they are dull.”

Because he thinks power is all about him, he seems unable to give others the space to be creative, which means that he can’t draw on the wisdom of those who are perhaps less clever than he is but have richer life experiences and more understanding of what makes others tick. And he seems to think that all he has to do is to make announcements. Power is also exercised through persuasion, and here he seems to have a major blind spot. As we know, he is very sensitive to voters’ opinions, but seems little interested in that of stakeholders. It is mind-boggling that his government decided to introduce a new mining tax without any prior consultation with the industry. Ambushing Australia’s most powerful industry in an election year is about as smart as Ben Chifley’s taking on the banks. Doesn’t he remember that the Australian Mining Industry Council’s advertising campaign killed the Hawke government’s commitment to national land rights legislation in the 1980s?

The battle with the miners has erupted since Marr finished his essay, but it is in character with the man Marr presents, a man for whom power is a brittle exercise in control and who has little understanding of the limits of what one person can do, even when he holds the highest office in the land. Perhaps Rudd will read Marr’s essay and learn from it. He does have deep intellectual and emotional reserves. And with an unelectable opposition, we would all be grateful if he showed signs of a maturing political judgement. But the concluding scene does not bode well for such an outcome.

Marr and Rudd have been chatting and Rudd asks him about the likely argument of the essay. Marr tells him that he is pursing the contradictions of his life, and wonders aloud if his government will go the way of Goss’s. Rudd explodes with controlled fury. It is, says Marr, the most vivid version of Rudd he has yet encountered. “Who is the real Kevin Rudd?” he writes. “He is the man you see when the anger vents. He’s a politician with rage at his core, impatient rage.” Marr’s essay is brilliant: it has all of the sharp observation and unexpected angles, and the lucid, supple prose, that make him such a fine interpreter of Australian political life. •